The foundation of every artificial intelligence system lies in its training data, yet few realize how dramatically skewed this foundation truly is. As AI systems increasingly shape global communication, commerce, and culture, the distribution of languages in training datasets has become one of the most critical yet overlooked factors determining who benefits from the AI revolution and who gets left behind.

Arabic is the fifth most spoken language globally, yet it accounts for less than 1% of AI training data (UNESCO). The historical overrepresentation of English and select other languages in AI research has created an uneven playing field.

arabic.ai

The Current Landscape of Language Distribution in AI Training Data

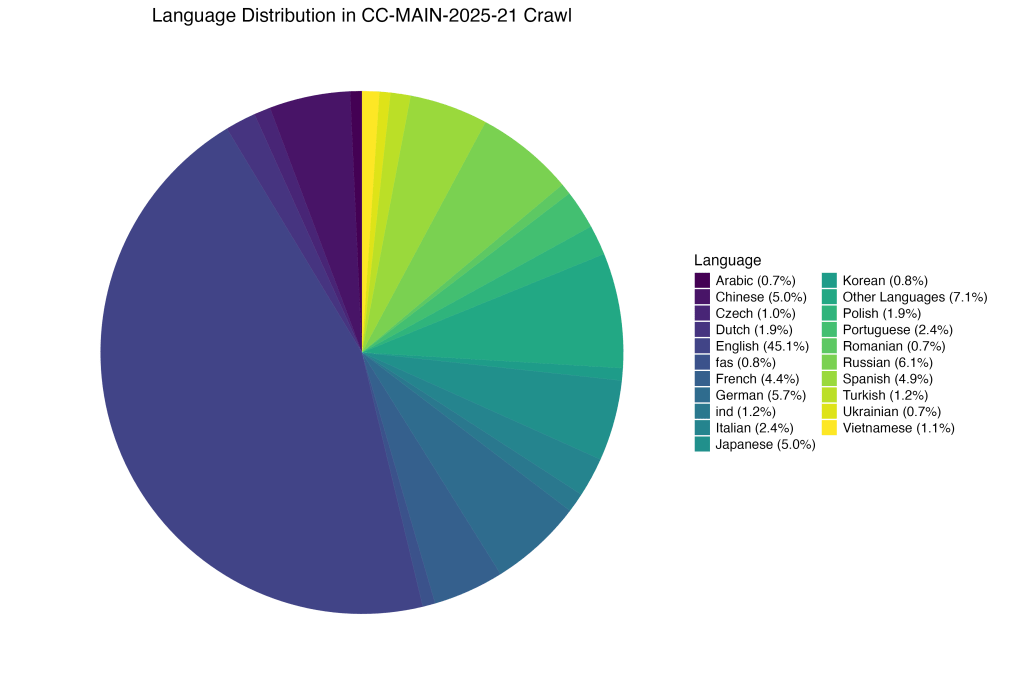

The statistics surrounding language representation in AI training datasets paint a stark picture of digital inequality. In the most widely used datasets that power today’s large language models, English maintains an overwhelming dominance that reflects neither global linguistic diversity nor population distributions. Common Crawl, one of the primary sources for training data, shows English comprising approximately 43.8% to 43.9% of all web content, followed by German at 5.1% to 5.5%, French at 4.2% to 4.3%, and Japanese at 4.8% to 4.9%. This concentration becomes even more pronounced when examining the actual training datasets derived from these sources.

The mC4 dataset, a multilingual variant of Google’s C4 corpus that includes text in 108 languages, demonstrates the scale of this disparity. While the dataset represents a significant effort toward multilingual inclusion, the token distribution reveals the depth of language inequality in AI training. English dominates with 2,733 billion tokens, while many other languages receive dramatically smaller allocations. For perspective, languages like Icelandic receive only 2.6 billion tokens despite serving 350,000 native speakers, while Telugu, spoken by 83 million people, has just 1.3 billion tokens.

Even in more deliberately balanced datasets, the English-centric bias persists. The ROOTS corpus, used to train the BLOOM language model, was specifically designed to improve multilingual representation by including 46 natural languages and 13 programming languages. Yet English still constitutes 30.03% of the data, followed by Simplified Chinese at 16.16%, French at 12.9%, and Spanish at 10.85%. While this represents an improvement over purely English-centric datasets, it still reflects significant imbalances that don’t align with global language usage patterns.

The Dominance of High-Resource Languages

The concentration of training data in a handful of high-resource languages creates a self-reinforcing cycle that amplifies existing digital divides. When researchers examine the underlying sources of training data, the pattern becomes clear: languages with strong digital presences, established tech industries, and significant online publishing ecosystems dominate the datasets. This dominance isn’t merely about raw volume but also about the quality and diversity of available content.

High-resource languages benefit from extensive digital infrastructure that produces varied, high-quality text across multiple domains. English, German, French, and Japanese content spans academic papers, news articles, literature, technical documentation, social media posts, and commercial content. This diversity enables AI models to learn nuanced language patterns, cultural contexts, and domain-specific vocabularies that enhance their performance across different use cases.

The challenge extends beyond simple representation to the quality of available data. Research evaluating web-crawled corpora across multiple languages reveals concerning quality disparities. While datasets like MaCoCu and OSCAR maintain relatively high quality for major European languages, the same cannot be said for all included languages. The mC4 corpus, despite its broad language coverage, shows quality issues where approximately one in five paragraphs has serious problems, including incorrect language classification or non-textual content.

The Plight of Low-Resource Languages

Low-resource languages face particularly acute challenges in the current AI training ecosystem. Research examining seven low-resource languages—Hausa, Pashto, Amharic, Yoruba, Sundanese, Sindhi, and Zulu—found that each constitutes less than 0.004% of the Common Crawl dataset. For languages spoken by millions of people, this representation is woefully inadequate for training robust AI systems.

The implications of this underrepresentation extend far beyond technical limitations. When Hausa, spoken by 80 million people across Nigeria, Chad, Cameroon, and Ghana, receives only 0.0036% representation in training data, AI systems struggle to provide meaningful services to these communities. Similarly, Amharic, the official language of Ethiopia and spoken by 60 million people, occupies merely 0.0036% of the crawled data, creating significant barriers to AI accessibility for Ethiopian users.

These disparities become even more pronounced when examining specialized datasets. In translation systems that rely on proportional sampling from mC4 data, languages like Lao receive only 0.003% representation, making it nearly impossible to develop effective AI tools for Lao speakers. The mathematical reality is stark: when training datasets allocate resources proportionally to existing web presence, they perpetuate and amplify existing digital inequalities rather than working to bridge them.

Quality Versus Quantity: The Complex Challenge of Multilingual Data

The challenge of creating representative multilingual datasets extends beyond simple collection to fundamental questions about data quality and processing. Translation, once seen as a potential solution for expanding language coverage, presents its own complications. While machine translation can theoretically multiply available training data across languages, the resulting datasets often lack the cultural nuances and contextual accuracy necessary for high-quality AI performance.

Research demonstrates that merely translating English content into other languages fails to capture the linguistic richness and cultural specificity that characterize authentic language use. Cultural contexts, idioms, colloquialisms, and regional variations cannot be adequately preserved through automated translation processes. This limitation becomes particularly problematic for languages with extensive inflectional systems or those that differ significantly from English in structure and cultural expression.

The preprocessing and cleaning stages of dataset creation also introduce biases that disproportionately affect certain languages. Filtering algorithms designed primarily for English content may inadvertently remove legitimate text in other languages that follows different structural patterns. Language detection systems, while capable of identifying over 100 languages, still struggle with accuracy for less common languages and can misclassify content, leading to inappropriate filtering or categorization.

Document length requirements and quality thresholds further compound these challenges. Requirements for pages to contain at least three lines of text with 200 or more characters may be appropriate for languages with Latin scripts but could unfairly exclude content in languages with different writing systems or structural norms. These seemingly neutral technical requirements often embed assumptions about language structure that privilege certain linguistic traditions over others.

Implications for AI Fairness and Global Accessibility

The unequal distribution of languages in AI training data has profound implications for global digital equity and technological accessibility. When AI systems perform poorly for certain language communities, they effectively exclude these populations from participating fully in the digital economy and accessing AI-powered services. This technological exclusion perpetuates existing socioeconomic disparities and can exacerbate global inequalities.

The digital divide refers to the unequal gap in access to and use of digital technologies, particularly the internet, across different groups and regions. This inequality impacts various aspects of life, including education, employment, healthcare, and social participation.

The consequences manifest across multiple domains. In healthcare, AI diagnostic tools trained primarily on English medical literature may fail to understand symptoms described in other languages or miss cultural concepts of health and illness. In education, AI tutoring systems may struggle to provide appropriate support for students learning in their native languages. In commerce, AI-powered customer service and recommendation systems may deliver suboptimal experiences for non-English speakers, limiting their access to global markets.

Financial institutions increasingly rely on AI for fraud detection, credit scoring, and customer service. When these systems perform poorly for certain language communities, they can create barriers to financial inclusion and perpetuate economic disparities. Similarly, AI-powered translation services, while designed to bridge language gaps, may actually widen them when they deliver poor-quality translations for underrepresented languages, leading to miscommunication and misunderstanding.

The quality disparities in training data create additional equity concerns. Research indicates that for many languages, only around half of available paragraphs meet publishable quality standards. This means that speakers of these languages may experience AI systems that provide inconsistent, unreliable, or culturally inappropriate responses, undermining trust in AI technology and limiting its beneficial applications.

Technical Solutions and Emerging Approaches

Addressing language inequality in AI training data requires both technical innovation and systematic policy changes. Researchers have developed several promising approaches to improve multilingual representation and quality. The UnifiedCrawl methodology demonstrates how targeted data collection can significantly increase representation for low-resource languages. By processing 43 Common Crawl archives specifically for seven low-resource languages, researchers achieved substantial improvements in dataset sizes compared to existing resources.

Advanced filtering and quality assessment techniques offer additional pathways for improvement. Rather than relying solely on automated translation, some approaches focus on identifying and extracting high-quality native content in target languages. Perplexity-based filtering methods can help identify authentic, well-formed text while excluding machine-generated or low-quality content that might pollute training datasets.

The development of language-specific preprocessing pipelines represents another promising direction. Instead of applying universal filtering criteria, these approaches adapt cleaning and extraction processes to the specific characteristics of different languages. This includes developing appropriate tokenization methods for languages without clear word boundaries, adjusting quality thresholds for different writing systems, and incorporating cultural and linguistic expertise in dataset curation.

Collaborative approaches to data collection also show promise. The BigScience ROOTS corpus demonstrates how international collaboration can create more balanced multilingual datasets. By involving researchers and native speakers from multiple language communities in the data collection and curation process, such efforts can better ensure cultural appropriateness and linguistic authenticity while achieving broader language coverage.

The Economics of Multilingual AI Development

Creating truly multilingual AI systems requires significant investment in data collection, processing, and quality assurance. The current market incentives often favor high-resource languages where immediate commercial returns are more apparent. However, this short-term thinking overlooks the substantial long-term benefits of inclusive AI development, including access to underserved markets and the social value of technological equity.

Organizations like Clickworker demonstrate emerging business models for multilingual data collection, utilizing distributed workforces of over 7 million contributors to generate, label, and validate AI datasets across multiple languages. These approaches recognize that high-quality multilingual training data requires human expertise and cultural knowledge that cannot be automated or translated. Similarly arabic.ai provides culturally sensitive models based on human curated high-quality multilingual training corresponding to Arabic’s linguistic richness .

The development of specialized datasets for specific languages and domains offers another economic pathway. Rather than attempting to include all languages in every dataset, targeted efforts can create high-quality resources for specific applications or language communities. This approach allows for more efficient resource allocation while ensuring that underrepresented languages receive appropriate attention and investment.

Future Directions and Emerging Challenges

As AI systems become more sophisticated and widely deployed, new challenges emerge around maintaining and improving multilingual capabilities. The phenomenon of “model collapse,” where AI systems trained on recursively generated data lose diversity and quality, poses particular risks for low-resource languages.

When limited authentic training data for these languages gets mixed with AI-generated content, the resulting datasets may become increasingly disconnected from actual language use.

The rapid growth of AI-generated content on the web creates additional complications for future dataset creation. As more online text originates from AI systems rather than human authors, maintaining access to authentic human-generated content becomes increasingly challenging. This trend particularly threatens low-resource languages where authentic digital content was already scarce.

Emerging approaches to multilingual AI development emphasize the importance of preserving and prioritizing human-generated content, especially for underrepresented languages. The value of authentic human interactions and culturally grounded text continues to increase as AI-generated content proliferates online. This creates new imperatives for proactive collection and preservation of linguistic diversity in digital formats.

Conclusion

The distribution of languages in AI training data represents one of the defining challenges of our technological age. While English and other high-resource languages benefit from extensive representation and high-quality datasets, billions of speakers of other languages face systematic exclusion from AI-powered services and opportunities.

This digital divide doesn’t merely reflect existing inequalities—it actively reinforces and amplifies them through technological systems that shape increasingly large portions of human experience.

Addressing this challenge requires coordinated effort from researchers, technology companies, policymakers, and language communities themselves. Technical solutions like improved data collection methods, quality filtering techniques, and collaborative dataset creation offer promising pathways forward. However, sustainable progress also demands changes in economic incentives, funding priorities, and development practices that currently favor high-resource languages.

The stakes of this challenge extend far beyond technical performance metrics. The languages represented in AI training data will largely determine which communities can fully participate in the digital economy, access AI-powered services, and benefit from technological advancement. As AI systems become more central to communication, commerce, education, and governance, ensuring equitable language representation becomes a fundamental requirement for technological justice and global development.

The path forward requires acknowledging that linguistic diversity in AI is not merely a technical challenge but a moral imperative. Creating truly inclusive AI systems demands sustained investment in multilingual data collection, quality assurance, and community involvement. Only through such comprehensive efforts can we ensure that the benefits of artificial intelligence reach all human communities, regardless of the languages they speak or the size of their digital footprint.

Bridging the Linguistic Divide in AI: Challenges and Pathways Forward

The exponential growth of artificial intelligence has spotlighted a critical yet often overlooked issue: the unequal distribution of languages in AI training data. While English dominates AI systems, billions of speakers of other languages face exclusion from equitable technological access. This summary distills key insights into why this disparity exists, its consequences, and actionable solutions.

What People Say

The Dominance of High-Resource Languages

English constitutes ~44% of web content used in datasets like Common Crawl, dwarfing languages such as German (5.1%) and Japanese (4.9%). This imbalance stems from the abundance of high-quality, domain-diverse English texts (academic papers, news, social media), enabling nuanced AI learning. By contrast, low-resource languages like Hausa (80 million speakers) and Amharic (60 million speakers) represent less than 0.004% of training data, crippling AI performance for these communities.

The Vicious Cycle of Data Inequality

Low-resource languages face a Catch-22: limited digital content reduces AI model performance, which discourages investment in further data collection. For example, machine translation systems for Lao (0.003% of mC4 data) struggle with accuracy, perpetuating underuse and stagnation. Even when data exists, quality issues plague 20% of non-English web-crawled text, including misclassified language or non-textual noise.

Technical and Cultural Barriers

- Structural Challenges: Languages like Japanese and Chinese lack word boundaries, complicating tokenization.

- Translation Limitations: Machine-translated datasets often miss cultural context, idioms, and regional variations, leading to flawed outputs.

- Filtering Biases: Preprocessing pipelines designed for English may discard valid text in other languages due to differing syntax or document structures.

Emerging Solutions

- Adaptive Training Methods: Techniques like Curvature Aware Task Scaling (CATS) dynamically balance gradients across languages, improving low-resource performance without harming high-resource accuracy.

- Targeted Data Collection: Projects like UnifiedCrawl focus on extracting high-quality native content for underrepresented languages, bypassing translation dependency.

- Collaborative Curation: Initiatives such as BigScience’s ROOTS corpus involve native speakers in dataset creation, ensuring cultural and linguistic authenticity.

- Synthetic Data: AI-generated synthetic data supplements scarce human-generated content for languages like Cherokee or Quechua.

The Road Ahead

Addressing linguistic inequity requires systemic shifts:

- Policy: Incentivize multilingual data collection through funding and regulations.

- Technology: Develop language-specific preprocessing tools and evaluation metrics.

- Collaboration: Partner with local communities and academia to build representative datasets.

Final Takeaway: Linguistic diversity in AI training data isn’t just a technical challenge—it’s a moral imperative. Without equitable representation, AI risks exacerbating global inequalities. By prioritizing inclusive data strategies, we can create systems that empower all language communities, not just the digitally dominant few.

Leave a comment