Open source software is not only a free resource but also gives people the opportunity to look at the underlying source code. Users can understand caveats or assumptions made by software and then eventually modify or adapt for their particular use. But what about packages or extensions? Are they also open source or partially licenced?

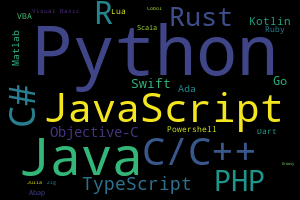

Within the world of statistical programming, R and Python currently dominate the landscape. Most developers use Python for its ease of use and ability to run on servers. According to a recent report by StackOverflow, Python is the preferred language package development. The PYPL (Popularity of Programming) confirms this by analysing how often a language tutorial is searched on an engine like Google.

Multiple repositories per language host packages that add to the functionality of the base language and are sometimes combined with package management tools helping to install and manage those add-ones.

Python and R lead the way with 395k (https://pypi.org/) and 18k extensions respectively.

Review and approval processes are required with thousands of developers contributing to individual packages. They have to ensure compatibility to the main language, other extensions and previous or potential future versions of those.

Python stands out because it does not have a review process. This mandates the need for due diligence on the part of the user, verifying assumptions and underlying data, and parameters of the packages used.

As opposed to Python the R repo CRAN is managed and requires specific details such as the inclusion of self-running tests, documentation according to a template, references of external material used and much more. A human looks at the proposed package after it passed the programmatical test, and the owner and authorship are recorded.

However commercial software users like SAS, SPSS and MatLab criticise the open-source landscape. Their argument is that with the diversity of packages available, there comes an opaque wave of assumptions, requiring the user to fully understand the underlying mechanics of every function call.

My first experience in contributing to the R repositories was challenged by the limitation of time given for automatic tests to run on included test data sets. However, this was back in 2018, so the rules may have changed since then. Back then, I was unable to identify how to include smaller sample data that would successfully return results in the time dictated by CRAN.

Later, I attempted to contribute to the ENM Tools Package from Dan Warren. I was keen to be able to add a multivariate method to what was an “ecological niche modelling” package.

I surrendered due to the requirements of having to comply with a vast, comprehensive set of conventions of this very well-designed toolbox to use standard input data, visualisations and output formats.

The only successful attempt I have had to date to contribute towards R repositories was being able to expand Hyndman’s linear model functions. I was able to do this in such a way that it catered for more combinations of population development scenarios.

As a third attempt, I was able to expand the linear model function proposed by Hyndman et al 2015 to incorporate more combinations of population scenarios.

Rob Hyndman developed an R function to estimate the existence and length of the time lag in species populations based on species occurrence time series. The method published in Biological Invasions detects a period of stagnant population growth prior to an increase. While the original script distinguishes species with biphasic population growth, this update fits a piece-wise model to differentiate between multiple scenarios. The script fits a maximum of 5 linear splines and determines the slope. The number of splines depends on the best model. Lag phases are reported if one or more splines have a slope of 0.

How does such a widely adopted programming language as python remains functional without a review protocol or even tests?

Leave a comment